When Death Comes

This article "When Death Comes" was published in the Australian magazine "Jimmy Hornet"

It was written by Karen Adler, an Australian, who visited New Zealand in 2023, when I did the interview, and again earlier this year.

“And did you get what you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.”

Raymond Carver

When Margaret Nelson died, her coffin was designed and created by her son, Mike, as per her wishes. As the only child, Mike knew beforehand that she wanted to be buried in a coffin with a big, bright, sunshine-yellow smiley face on each end. When Mike told me this, I laughed out loud, assuming he was joking. But no, this was how his Mum was, who she was. And she was a woman who knew what she wanted. Just after this revelation about Margaret, Marisa Nelson, Mike’s wife, recalls her wearing two totally different earrings,

deliberately pulling on mismatched socks, just to bring a little light and lightness into

people’s lives, including her own.

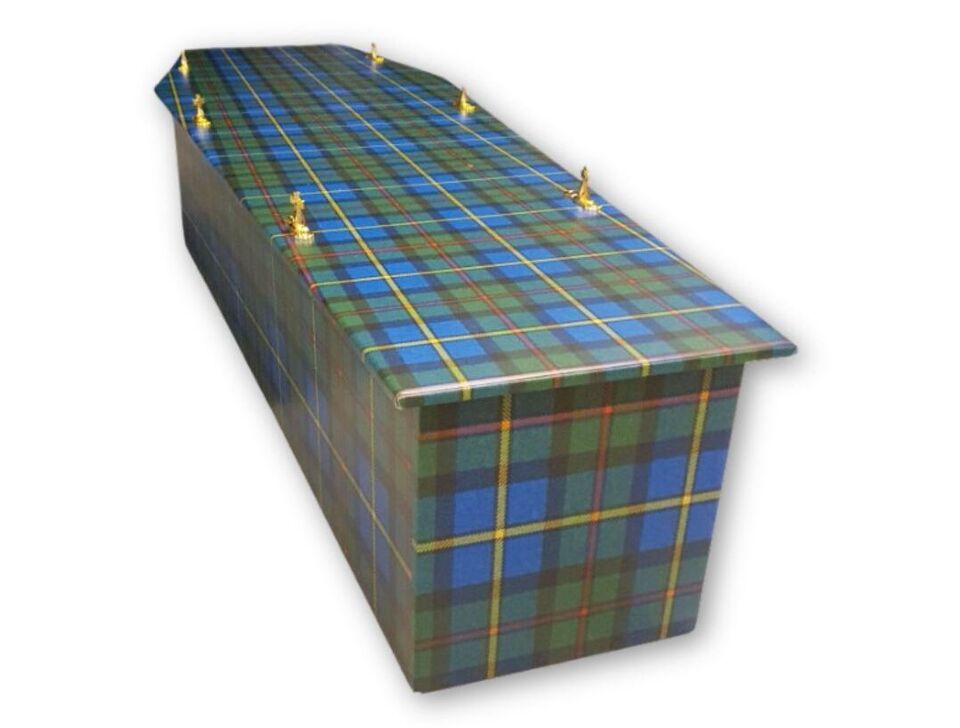

The interview I conduct with Mike and Marisa, who jointly runs the business, is unexpectedly - and very delightfully so - full of hilarity. One of the things that drew me to them in the first place was their business name - Carried Away NZ - which made me laugh the moment I read it. This theme of black humour runs through our chat as I discover the origins and later, the very deep roots, of Carried Away, which originated in that undertaker’s office in 2016. It was this meeting that fuelled Mike’s desire to create coffins that are affordable for ordinary folk.

But wait there’s more, adds Mike with glee. There were also multitudes of iridescent, pearlescent bubbles, generated by Mike with a bubble machine, floating around this beautiful farewell.

So I have in my imagination, this final scene of a bright sunshine yellow coffin, big bold smiley faces on each end, balloons bouncing slightly above the verdant green New Zealand grass, bubbles catching sunlight, creating rainbows. I would wish this version of a goodbye to those we love, for all of us, including myself.

This honouring of Margaret’s wishes, this recognition of who she was, is what Carried Away offers to people - that they too, can create a farewell for someone they love that’s personal and individual, a final way of saying what they want to say, what they need to say.

Mike and Marisa have many examples of people having done exactly this. One of the most poignant is of a father who died, leaving behind his wife and young children. His wife set up one of Carried Away’s plain MDF coffins in the garage on two wooden trestles, which her husband had no doubt used for home handyman jobs. She and the children spent the day decorating his coffin, creating for themselves a memory of making one final gift for this most important person in their lives. They adorned it with toy motorbikes, a pristine white baseball cap with his name on it, a family photo with Santa, hearts, rainbows, stars, small handprints covered in paint and pressed onto the surface, messages of love to him from

them.

One of the things we talk about in this rambling conversation, full of dark humour - ‘dead right!,’ Mike says to me at one point and I wonder out loud how to work it into this Jimmy Hornet article [tick ✔ ] - is that despite knowing death is inevitable, it’s still hard. It doesn’t matter how old we are or how old our family or friends are when they die, if there was love between us, it’s the hardest thing in the world to accept that we’ll never see them again, never speak with them, never laugh or cry together.

My interest in death and how to do it well, stems from my mother’s death. Mum was my best friend for my whole life. When she died, I was only 35, she was only 63. I had no idea that her death would almost destroy me, that I would wish to follow her into the grave, that it would derail my life, take me years and years to get over it, that it isn’t really the sort of thing you ‘get over’.

After Mum died, after a year of broken-hearted crying, of dreading each new dawn, knowing I’d wake to her not being in my world, I eventually saw a psychologist. Jocelyn listened to my story and diagnosed me with ‘complicated grief’.

The results of a blood test showed no evidence of depression. I now know but didn’t at the time, that this is impossible - there are no physical tests that provide such proof. Despite this lack of evidence, I was prescribed antidepressants - which I now see as a mixed blessing. At the time, they enabled me to dull my emotions sufficiently to limp my way through each day. Over the next few years, with changes in my medications, trying to go off them, I experienced horrendous adverse reactions that I never associated with the meds. This exacerbation of my symptoms - the nightmare roller coaster ride of highs and lows, dulled-out thinking, the impossibility of making decisions, through-the-roof anxiety, uncontrollable body tremors - isn’t uncommon. Many people experience them. Many self- medicate with alcohol, recreational drugs - as I did - and assume their depression/anxiety is getting worse. Some end up in psych wards, some suicide.

I now see, with the blessed wisdom of hindsight, that much of what happened to me after Mum’s death, was preventable. I now know that if I’d had different tools, different knowledge, different doctors, my mother’s death would have been very different than it was. ‘Wish in one hand and spit in the other, Karen, and see which fills up faster,’ as my very practical Mum often said to me as a child. And no, I can’t change the past - couldn’t then, can’t now.

But I used what I learned about death when my father died nineteen years later. That same wise psychologist had given me a small book on grief by a Catholic priest, along with the prescription she gave me. The most significant and life-changing thing I learned was that grief is such a powerful emotion, it generates toxins in the body - chemical interactions, that unless regulated in some way, cause havoc on our nervous systems.

These toxins are released via our tears. I found this to be a remarkable piece of design. After my Dad died, rather than travel the nightmare road of natural sorrow becoming unnatural depression, I cried at the drop of a hat - every day, whenever I needed to, no stiff-upper-lipping. I cried so much and so loudly that my next door neighbour, Dee, knocked on my door one morning when she heard me howling in the shower, to check that I was okay.

Death Café is another tool that, if I’d had it at the time, would have made Mum’s death easier for me. What made her death so hard was that she was my best friend, yes, but also that I didn’t expect her to die, even though she’d been on home dialysis for kidney disease for years. Apart from light-hearted lines such as, ‘When I die, you can just put me up a hollow log,’ we’d never really talked about her dying.

The roots of Death Cafés go back to 1999, when Swiss sociologist, Bernard Crettaz, held a ‘café mortel’ to discuss death after his wife died. A few years ago, I co-hosted two Death Cafés on the Central Coast in Australia. Attendees shared information we’d gained from experiencing - and by inference, surviving - the deaths of people we loved. For my own death, I envisaged an Ophelia-like scenario - me floating down a flower-strewn river, dressed in something white and diaphanous, preferably without the preceding scene of

grief-induced ‘madness’ leading me to suicide.

I used the Raymond Carver poem at the beginning of this essay, at my father’s eulogy. Dad and I had a very different relationship than Mum and I - he found it difficult if not impossible, to express his feelings. Mum and I were the exact opposite - mother-daughter talks and deep and meaningful’s were our thing and it was many years after she died that I realised how left-out my father must have felt. I chose Tim McGraw’s ‘Live Like You Were Dying’ as his funeral song. I only discovered much later, via reading his Advance Care

Plan, that Dad had requested a traditional Catholic funeral. Oops. Soz, Dad.

I’m in New Zealand at the moment. I love how well the Maori culture is incorporated into the NZ landscape - literally, in that most places of significance in this stunningly beautiful country are accompanied by Maori carvings depicting the travels of Gods and Goddesses. And also metaphorically - I sense a deeper respect for Maori culture and the endeavour by both Maori and Pakeha to walk together through difficult terrain of past injustices and current land ownership problems, than I see in Australia.

Humans have been performing rituals from the moment we set foot upon the Earth. A Kiwi friend, Bush, told me about the Maori tradition of unveiling the headstone [hura kōhatu] a year after a person has died. Family and friends of the deceased make a journey from wherever they are to the hura kōhatu, to remember the person’s presence in their lives.

As my father did, religiously, every anniversary, birthday, Christmas, after my mother died. Dad drove the five hours from Rubyvale to Rockhampton, Brasso and well-used rags in a small cardboard box in the boot of his car, to polish my Mum’s plaque. A quote from St. Exupery’s time-honoured classic, ’The Little Prince’, is on her plaque. ‘We will look for your star’. These six words are about grief inevitably passing and finally being able to remember the person you loved as your friend who now resides in the night sky - everywhere, every night, always.

Last week, I visited the Waitangi Treaty Grounds. One of the many multimedia storytelling displays spoke about Maori funerals - ‘tangi’ in the Maori language. ‘Tangi means to cry, to wail but it also means, to celebrate. Let that be the tangi in Waitangi.’

If we can learn to embrace both the darkness and the light of life, the beginnings, the endings and everything in between, our lives will be lightened. And when death comes, as it inevitably will, we can leave this Earth more willingly, with more peace, less struggle - and maybe, like Margaret, with some iridescent bubbles glistening in the sunshine and some balloons bobbling along over the grass, making people laugh at the same time as

they cry.

©Karen Adler, 2024

Word count: 2153 words

References:

https://www.carriedaway.kiwi.nz

McGraw, Tim. Live Like You Were Dying,

Stilling, Rosalyn. Drowning in Womanhood : Ophelia’s Death as Submission to the Feminine Element, https://www.nicholls.edu/cheniere/wp-content/uploads/sites/

71/2019/07/Stilling-Paper-Final-Version-1.pdf

Posted: Tuesday 10 December 2024

Recent Posts

Archive

| Top |